|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

PREVENTION AND

CONTROL OF HEPATITIS B IN CENTRAL

AND EASTERN EUROPE AND THE NEWLY

INDEPENDENT STATES

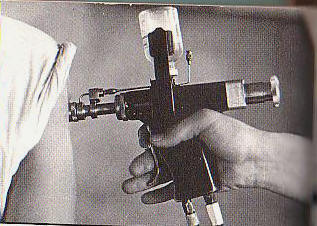

Various routes of transmission of HBV to patients have been documented, including transfusion of contaminated blood and blood products, use of jet gun injectors with a design fault that allowed blood to remain inside the equipment, re-use of contaminated needles and syringes, and indirect transfer from contaminated environmental surfaces in haemodialysis units....

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. Hepatitis B 2.1 Virology of hepatitis B virus 2.2 Clinical features of hepatitis B 2.3 Hepatitis B vaccines 2.4 Prevention and control policies 2.5 Epidemiology of hepatitis B 2.5.1 Global morbidity and mortality 2.5.2 The epidemiology of hepatitis B in the region 2.5.2.1 Prevalence and incidence data 2.5.2.2 Overall picture 2.5.2.3 Low prevalence countries 2.5.2.4 Intermediate prevalence countries 2.5.2.5 High endemicity countries 2.5.2.6 Hospital-acquired infection 2.6 Strategies for prevention of hepatitis B 2.6.1 General preventive measures 2.6.2 Standard precautions 2.6.3 Vaccination strategies 2.6.3.1 Selective vaccination 2.6.3.2 Universal vaccination (a) Adolescents (b) Infants (c) Infants, adolescents and those at high risk 2.6.4 Promoting vaccination 2.7 Priority setting 2.7.1 Disease burden 2.7.2 Cost effectiveness 2.7.3 Information and education 2.7.4 Strategy 2.7.5 Disease burden in Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan 2.8 Health economics 2.9 Resource mobilization 2.9.1 Increased government financing 2.9.2 Setting priorities for funding and services 2.9.3 Affordability

2.9.4 Support 2.10 Workshops 2.10.1 Resource mobilization 2.10.2 Monitoring and surveillance 2.10.2.1 Lack of comparability of surveillance data between countries 2.10.2.2 Assessing the burden of disease due to hepatitis B virus infections 2.10.2.3 Monitoring the effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination programmes 2.10.3 Vaccines and immunization 2.10.4 Vaccine production, quality control and regulatory issues 2.10.5 Nosocomial transmission 2.10.6 Diagnostics 2.10.6.1 Sensitivity of assays 2.10.6.2 Specificity of assays 2.10.6.3 Rapid, instrument-independent assays 2.10.6.4 Reduction in post-transfusion hepatitis B

3. Consensus and conclusion 3.1 Data 3.2 Constraints 3.3 Immunization programme 3.4 Consensus

Annexes: Annex 1 : consensus statement (Russian version) Annex 2 : consensus statement (English version) Annex 3 : List of participants

Table 1: Endemicity of hepatitis B virus infection in central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States in terms of prevalence of HBsAg Table 2: Data on demography, markers of hepatitis B virus infection and immunization policy in central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States Table 3: Sustainable vaccine supply: banding of counties for global targeting strategy Table 4: Relative sensitivities of assays for the detection of HBsAg Table 5: Performance characteristics of flow-through and lateral-flow devices Table 6: Comparison of test characteristics Table 7: Post-transfusion hepatitis B in regions of different HBV endemicity with and without flow-through screening of blood donations

Fig 1 Prevalence of HBsAg in central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States Fig 2 Sustainable vaccine supply: global targeting strategy for central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States

1. INTRODUCTION

The prevention and control of hepatitis B constitute a major policy priority especially in the countries of central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States, many of which report high prevalence rates of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and of clinical disease. For some 15 years safe and effective vaccines against hepatitis B have been available. Previous attempts to prevent and control the disease have rested on the strategy of immunizing people at highest risk of infection, such as health-care workers, but no country has succeeded in controlling HBV infection with this strategy. This failure has led to the recommendation of universal childhood immunization as the most effective way to decrease infection rates and to lower the amount of acute infection.

The Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board jointly organized with the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) a meeting to bring together managers of immunization programmes, national hepatitis experts and senior officials from ministries of health. The meeting was held with the active support of the Hungarian Ministry of Health in Siófok, Lake Balaton, Hungary, on 6-9 October 1996.

The aim of the meeting, on which this report is based, was two-fold: to put the prevention of hepatitis B on the political agenda and to speed the progress of the countries in central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States towards the implementation of universal childhood immunization against hepatitis B. In particular, its objectives were to summarize and share available data, to identify what is necessary for the implementation of a strong programme against hepatitis B, and to highlight the main constraints against such action in the region.

This conference was the first to focus on hepatitis B control and prevention with the inclusion of all the countries in the region, and afforded a major opportunity to raise awareness of hepatitis B with decision-makers and to discuss with them the introduction of hepatitis B vaccination into universal immunization programmes. The high level of participation - in many cases Deputy Ministers of Health or Deputy Chief Medical Officers attended - testifies to the importance accorded to the matter by the health authorities of the countries concerned. The joint sponsorship of the meeting attested to the willingness of the organizing bodies to help in the implementation of prevention and control programmes and to assist in the identification of donors to help secure supplies of vaccine.

In 1991 the WHO called for all countries to implement hepatitis B into their immunization programmes and so far more than 85 have done so. This figure includes only 5 of the 25 countries in the region under discussion. The VHPB, an independent, international and multidisciplinary group of experts set up to consider, make recommendations and encourage action to improve the control and prevention of viral hepatitis in the WHO European region, has been actively supporting the WHO’s position. The CDC have been committed to the control of viral hepatitis world-wide for several years and have worked to provide technical assistance to countries that request help in the areas of prevention and control.

Following the dissolution of the USSR, many countries who had received their routine vaccines (DTP, polio, measles and BCG) from Russia found themselves without a supply of vaccines which they could afford. Although donors were found to supply infant routine vaccines, no provisions were made for hepatitis B vaccines, even though the burden of disease from HBV infection was greater than that of other vaccine-preventable diseases in many areas. This situation prompted the convening of the Siófok meeting to consider ways of facilitating the inclusion of routine hepatitis B immunization in national immunization programmes of these 25 countries in the region (no representatives from Bosnia and Herzegovina and from Yugoslavia attended the Siófok meeting).

2. HEPATITIS B 2.1 Virology of hepatitis B virus Hepatitis B is caused by hepatitis B virus, a DNA virus of the genus hepadnavirus containing a partially double-stranded circular DNA genome and three major antigens: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), the core antigen (HBcAg) and a derivative of the latter, namely the e antigen (HBeAg). It also contains a DNA polymerase. The icosahedral viral particle has a diameter of 42 nm. Although four subtypes of HBV due to antigenic variation in HBsAg are known, infection with one strain confers resistance against all strains.

HBV is mainly hepatotropic; it attaches through its HBsAg to liver cells in which its DNA is converted into RNA, from which new DNA viral particles are synthesized and released by budding. The virus is not cytopathic but triggers liver damage through the immune response to infected hepatocytes. Symptoms of infection appear after a lengthy incubation period of 1-3 months.

The virus itself is robust. It can survive on surfaces such as surgical instruments, chairs and work benches for as long as one week at room temperature. It is about 100 times more infectious than HIV.

The natural hosts of HBV are human beings; there is no other reservoir. HBV is present in high concentrations in blood, serum and wound exudate. It may also be present in moderate concentrations in semen, vaginal fluids and saliva. It is either undetectable or present in small amounts in urine, faeces, sweat, tears and breast milk. Thus, the main routes of transmission are parenteral, sexual, from mother to child (vertical or perinatal) and horizontal.

Transfusion of blood from HBsAg-positive donors is one of the most efficient means of transmitting HBV. A WHO study in 1990 indicated that more than 43% of the world’s population lives in regions where blood is never or only sometimes screened for HBsAg, and for another 11% of the world’s population no data are available on blood screening practices. In the WHO’s European Region only 28% of blood donations were always tested for HBsAg, with no information on the testing practices for the remaining 72%.[1] The high cost of importing sensitive and specific tests such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays is probably the biggest constraint on testing of blood.

Among health-care workers exposed to needlestick injuries the minimum volume of blood from a patient infected with HBV needed to transmit infection is 0.04 µl. The risk of infection after a needlestick injury with a HBV-positive patient lies between 7% and 30% or higher, the rate depending on whether the blood is positive for HBeAg. (A CDC study showed that 37-62% of health-care workers exposed to HBeAg-positive blood showed markers of infection and 22-31% developed clinical acute hepatitis.) The average volume of blood inoculated during a needlestick injury with a 22 gauge needle is about 1 µl which can contain up to 100 infectious doses of HBV.

Contaminated equipment such as used in tattooing, earpiercing and acupuncture can lead to transmission. Heterosexual transmission occurs, and may be facilitated by the presence of genital ulcers. High rates of infection are seen in injecting drug users, homosexual men and in the general population in many developing countries as a result of sexual transmission. Horizontal transmission between children also occurs and in Asia transmission from mothers to children (vertical transmission) is even more prevalent, and represents therefore a serious problem.

2.2 Clinical features of hepatitis B HBV infection has different clinical manifestations depending on the person’s age at infection, immune status and the stage at which the disease is recognized.

In infants and young children most HBV infections are asymptomatic; only some 5-10% of neonates show symptoms. Irrespective of the development of symptoms, most infections (70-90%) progress to the chronic carrier state, with about 30-50% of these people developing chronic liver disease: cirrhosis and primary liver cancer.

Although about a third of adults infected with HBV are completely without symptoms, another third present with a ‘flu-like illness without jaundice; in them HBV infection is rarely diagnosed. The rest of those infected present with typical signs and symptoms of viral hepatitis, including jaundice, dark urine, extreme fatigue and pain in the right upper quadrant. Activities of liver enzymes, for example alanine aminotransferase, are often much greater than normal and the serum concentration of bilirubin is also markedly raised. Among those with symptomatic infection less than 1% develop fulminant hepatitis, but this condition carries a very high mortality.

Most infected adults recover completely and develop lifelong immunity against the virus, but some 6-10% fail to eradicate HBV and become chronic carriers and thus infectious, often for life. In about a quarter of those who become carriers chronic HBV infection can lead to progressive liver disease. Progression to chronic hepatitis depends on continuing viral replication in the liver and on the host response. When HBV replicates chronic active hepatitis develops and can lead to cirrhosis. Chronic infection can also cover a long stage of quiescent liver disease, with primary liver cancer developing 20-30 years after infection with HBV.

When a person is infected with both HBV and hepatitis D virus[2], the latter infection may be self-limited as the virus cannot outlive the transient HBV infection. However, superinfection of a chronic carrier of HBV with HDV may lead to fulminant disease, but severe chronic hepatitis with an accelerated progression to cirrhosis is more likely.

The most important factor predisposing to the development of the chronic carrier state is age at infection. During perinatal infection maternal HBV antigen and antibodies may suppress the infant’s own immune response which in any case will be immature and unlikely to mount an effective response against HBV antigens. Other factors include male gender, immunosuppression through use of steroids or other immunosuppressive drugs and immunodeficient conditions such as cancer and HIV infection. Immunodeficient people infected with HBV tend to develop a milder disease but are more likely to become carriers than immunocompetent ones.

2.3 Hepatitis B vaccines Hepatitis B vaccine consists of HBsAg. The first-generation vaccines were derived from the plasma of chronic HBV carriers. The reason for this unusual approach to a vaccine is that HBV could not, and still cannot, be grown in cell culture. The various difficulties raised by the production of a vaccine from human plasma spurred the search for alternatives. The gene for HBsAg can be expressed now in both yeast and mammalian cells, producing a protein identical to that in the plasma-derived vaccine except that it is not glycosylated. Nevertheless, as a vaccine, the immunogenicity, efficacy and safety of this recombinant protein are the same as those of the natural product.

Despite the experience of their use over 15 years, some questions about the use of hepatitis B vaccines remain unanswered. How long does protection last? Are booster doses needed? What is the position regarding people who do not respond to hepatitis B vaccination? How can we protect against mutant forms of HBV?

Antibodies to HBsAg peak about 4-6 weeks after the final dose of vaccine and decrease in concentration rapidly at first but progressively more slowly. Immunization produces neutralizing antibodies that protect against HBV infection but it also induces efficient and long-lasting immunological memory that allows protective responses after antibodies have disappeared. Thus immunity lasts longer than the persistence of antibodies. Recommendations for revaccination to boost immunity can be relaxed. In general there is no clear evidence of the need for booster doses after primary series of vaccination has been completed. Long-term studies (field experience extends to 10-12 years) in high-risk newborns demonstrate that protection against acute disease and development of a chronic carrier state lasts beyond the fall of antibody levels. However, booster doses are recommended in the package insert accompanying the vaccine in some countries, and may be indicated in particular situations such as immunocompromised patients or health-care workers. Testing for anti-HBs after vaccination may be recommended for health-care workers who need to know whether they are protected.

Some 3-5% of people vaccinated do not produce specific antibodies after a normal course of immunization. Although some immunodeficient people have seroconverted when interleukin-2 has been administered with the vaccine, the procedure is ineffective in immunocompetent subjects. Additional doses of vaccine can induce immunity. With up to three additional doses, about half of the non-responders eventually seroconvert.

Several escape mutants of HBV have been discovered but most have no biological or medical significance. Some, however, especially those with mutations in the a determinant of HBsAg, may resist the immune response. Consequently some doubt has been cast on the effectiveness of present HBV vaccines, but these mutants do not appear to be new or to pose any real danger. “Real” escape mutants have not been observed.

2.4 Prevention and control policies Prevention and control of HBV infection are now major health priorities, especially since safe and effective vaccines have been available for more than a decade. In 1991 the WHO called for all countries to include hepatitis B vaccination in their national immunization programmes by 1997. Routine immunization of infants is recommended for countries with a prevalence of chronic HBV infection of 2% or higher, and countries with lower rates may adopt immunization of adolescents instead of or in addition to infant immunization. So far, more than 85 countries world-wide have included hepatitis B vaccination in their national programmes.

In the WHO European Region more than a million people acquire hepatitis B each year, of whom about 90,000 will become chronic carriers of HBV. In the 25 countries in central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States (NIS), many of which have high incidence rates of HBV infection, only five have yet included HBV in their national immunization programmes. The other countries have failed to do so mainly because of economic constraints.

2.5 Epidemiology of hepatitis B 2.5.1 Global morbidity and mortality Globally at least 2000 million people have been infected with HBV at some time in their lives and about 350 million are chronically infected. The general public recognize HBV as a cause of jaundice but it is not widely known that the virus is the major cause of death from cirrhosis and chronic liver disease including liver cancer. Chronic hepatitis B infection is responsible for at least 60 million cases of liver cirrhosis world-wide, more than the number of cases caused by alcohol. HBV infection is responsible for more than one million deaths a year, and most of these result from its chronic manifestations. According to a study in women in Taiwan the relative risk of developing liver cancer is 10 times greater than that of smokers developing lung cancer.

2.5.2 The epidemiology of hepatitis B in the region 2.5.2.1 Prevalence and incidence data Several epidemiological measures are used to describe the burden of disease for HBV infection. The most commonly used indicators are the prevalence of HBV carriers in the population and the incidence of acute clinical hepatitis B. Three categories of prevalence have been described: low (with <2% of the population carrying the HBsAg marker), intermediate (2-8%) and high (>8%). The prevalence of carriers indicates the size of the pool of infectious people and those at risk of the chronic sequelae of HBV infection, namely cirrhosis and primary liver cancer. The distribution of prevalences in the European region is shown in Table 1 and Fig 1.

Prevalence data need to be interpreted with care, for some of the studies used to determine prevalence rates may be seriously biased. For instance, data on blood donors are readily available but this group may be very unrepresentative of the general population because of donor self-selection, socio-economic or cultural bias about who donates blood, prior screening to eliminate HBsAg-positive people from the donor pool, or the use of paid donors.

Incidence data for acute clinical hepatitis B are even more unreliable than data on the prevalence of carriers of HBsAg. No two countries, even in Western Europe, measure the incidence in the same way and there is no comparable standard case definition across Europe.[3] The type and nature of reporting vary widely. Differences in reporting criteria range from countries that report jaundice cases without serological differentiation to countries that report hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. Some countries mix reporting of HBsAg carriers with that of cases of acute clinical hepatitis B. Many countries do not have reagents available to differentiate types of viral hepatitis and diagnosis is based on physicians’ instincts or guesses. Some countries base their reporting on clinical cases whereas others rely on laboratory reports. Still others use sentinel surveillance systems. The degree of under-reporting is significant and differs for each country. As hepatitis B is mainly an asymptomatic infection, this will play an additional role in the under-reporting.

TABLE 1 Endemicity of hepatitis B virus infection in central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States in terms of prevalence of HBsAg (no data available for Bosnia and Herzegovina and for Yugoslavia)

Low (<2%) Intermediate (2-8%) High (>8%)

* Hepatitis B vaccination included in national immunization programme + Hepatitis B vaccination included in national immunization programme but implementation subject to financial constraints

2.5.2.2 Overall picture Most countries of northern and western Europe have very low prevalences of HBV infection (with rates of less than 0.5% of the population carrying HBsAg). Incidence rates too are very low, being less than 1/100,000 in the general population in Scandinavia, Ireland and the UK. The rates increase southwards (incidence rates rising to about 6/100,000) but eastwards and south-eastwards the picture is very different. The virus is highly endemic in some eastern European countries and the Newly Independent States, especially the Central Asian Republics; carriage rates of HBsAg rise to 2-7% in central and eastern Europe and more than 8% (high endemicity) in the Central Asian Republics. Table 2 summarizes more detailed data acquired through questionnaires distributed to participants before the meeting.

Hepatitis D infection is present; in Central Asian Republics up to 20% of cases of HBV infection also have D infection. Here little HBV-related carcinoma is seen, for the simple reason that people die of D superinfection (and short life expectancy) before the carcinoma can develop. Rough estimates put the number of deaths from HBV-related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma at about 200 a year in north-west Europe but about 18,600 in central and Eastern Europe.

2.5.2.3 Low prevalence countries The lowest prevalence rates outside western European countries are seen in the northern parts of Central and Eastern Europe, the Baltic republics and Armenia (see Table 2). Reported incidence rates in these regions range from 1 to 25 cases per 100,000 population a year. Although this is called ‘low’ endemicity relative to other areas of the world, this does not imply a low burden of disease, and hepatitis B continues to be a major infectious disease problem.

Screening of blood donors in Croatia has shown a falling prevalence of HBsAg positivity, from 1.53% in 1982 to 0.34% in 1991 and, after a rise, to 0.32% in 1995. There, immunization is compulsory for health workers exposed to infection as well as for at-risk people. The Czech and Slovak Republics as well as Hungary have HBsAg prevalence rates of less than 1%. Higher rates are seen in Armenia, Poland, Ukraine and Slovenia but in several countries the rates are declining. For instance, whereas the incidence rate of acute hepatitis B in the general population in Slovenia in 1992 was about 6/100,000 it fell to 0.9/100,000 by October 1996. Data for Ukraine for 1993-95 show an incidence of hepatitis B of 24-25 cases/100,000 population, with highest rates in the under-1 year and 20-30 age groups. HBsAg carriage was 1.1% among blood donors but 2.3% among at-risk groups such as health workers and injecting drug users. In Armenia screening of blood donors identified 1.25% carrying HBsAg in the first 9 months of 1996, a figure similar to that in the previous 6 years, whereas the incidence of acute hepatitis B fell from 23.1/100,000 in 1990 to 9.7/100,000 in 1996.

2.5.2.4 Intermediate prevalence countries Intermediate prevalence rates of 2–7% are seen in the southern and eastern parts of central and eastern Europe, a finding not appreciated in the West until the fall of communism in this area. According to the national participants at the meeting, both the acute and chronic sequelae of hepatitis B make it one of the most important infectious disease problems in their countries. Most experts believe that perinatal transmission is uncommon and that horizontal, sexual and especially nosocomial transmission accounts for incidence rates that range from 25 to 100 per 100,000 population a year.

In The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia blood-donor screening showed a prevalence of 2.0% in the years 1992-95 while the incidence of all viral hepatitides was 109/100,000. In Bulgaria HBsAg carrier prevalence is 3-5% and 20% of the population have evidence of exposure to HBV. The incidence rate of chronic HBV infection is high, 30.3/100,000, with a mortality rate for chronic liver disease and primary liver cancer of 24/100,000. Belarus recorded some 4100 carriers of HBsAg by August 1996 (39.8/100,000). Georgia has seen a decline in reported cases of all hepatitides, the total falling to about 7000 in 1994, with 19% due to hepatitis B or D, but it is recognized that the decline is almost certainly an artefact of reporting, consequent on the disruptions around independence and continuing through unaffordability of medical care for many people. The extent of transmission of hepatitis B, C and D through injecting drug use, occupational exposure among health-care workers, blood transfusion and unsafe sex is "anybody's guess".

In the Russian Federation generally, the proportion of cases of hepatitis B among all reported viral hepatitides is steadily increasing, reaching about 30% in the first 8 months of 1996. Incidence rates have doubled between 1992 and 1995. Low and intermediate prevalences are found across the huge country; HBsAg carriage rates range from 0.3% in the Tula oblast to 6.4% in the Tyva republic. Among newborns across Russia in 1994 3.1% were carriers of HBsAg. In far-eastern Russia the prevalence rate of HBsAg carriage is considered to be 5%.

Before Romania introduced hepatitis B immunization into the national immunization programme in 1995 the prevalence of HBsAg in the general population was 5.95% (with an anti-HBc prevalence of 31.0%) and the incidence rate of hepatitis B infections was 24.4/100,000. By mid-1996 the incidence rate had fallen to 9.96/100,000, with a more than 2.5-fold reduction in the 1-14 year age group.

2.5.2.5 High endemicity countries While endemicity and morbidity due to hepatitis B lie in the intermediate range in central Russia, in some regions such as central and eastern Siberia, the Caucasian regions and the Central Asian Republics they are high, with prevalence rates of HBsAg of 11.1% in Kyrgyzstan in 1994 and 15.6% in Turkmenistan in 1995. Reported incidence rates of hepatitis B vary from 23.6/100,000 in Kazakhstan in 1994 (rising to 26.8/100,000 in 1995) and 98.5/100.000 in Uzbekistan in 1995 to 300-400 cases/100,000 in eastern Siberia and about 400/100,000 in Turkmenistan in 1994 (where the peak rate was reached in 1984 when about 1% of the population had jaundice due to HBV). One can only guess at the number of subclinical cases in these regions. Transmission patterns vary too. A study in Ashgabat (Turkmenistan) in 1994 revealed that in 70% of cases of hepatitis B there had been no known parenteral exposure. In Moscow in contrast no parenteral exposure was determined in only 13% of cases.

In Albania the HBV situation was described as very grave and dangerous, with prevalence rates similar to those in the hyperendemic countries of Asia and Africa. The Albanian Ministry of Health at the time of the meeting concluded that the only effective intervention is universal vaccination.

TABLE 2: Data on demography , markers of hepatitis B virus infection and immunization policy in central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States

HCW: health-care worker HRG: high-risk groups

2.5.2.6 Hospital-acquired infection HBV is transmitted nosocomially by three primary routes: 1. patient to health-care provider 2. patient to patient via contaminated equipment, and 3. from provider to patient. The risk of transmission from patient to health-care worker is well recognized and, before the introduction of vaccination, was primarily related to the frequency of blood contact in the workplace. The second route has been less commonly reported but may account for a substantially higher proportion of the overall disease burden associated with hepatitis B world-wide. It results mainly from the re-use of contaminated medical and dental equipment such as needles and other sharp instruments. Transmission from health-care provider to patient is infrequent and primarily results through surgical invasive procedures by infected surgeons.

Among hospital personnel the prevalence of HBV infection was associated with increasing years of work and exposure to blood. Rates vary by job category. Highest rates, about 25-30%, are found in nurses working in emergency rooms (accident and emergency departments) and in blood technicians who had a high frequency of blood contact; other nurses and auxiliary staff also had high rates. The lowest frequency, 5-6%, was found in dieticians and ward nurses who had infrequent blood contact. Most needlestick injuries are associated with a limited range of activities, namely administration of injections, drawing blood, recapping needles after use, disposal of used needles and handling waste material containing uncapped needles.

In some of the countries in eastern and central Europe and the Newly Independent States hospital-acquired infection with HBV is a significant problem. Poland, for example, has one of the highest incidence rates in the region, about 35/100,000 in 1993 but the rate among health workers was about 4 times higher. More than 60% of cases and 80% of those in children were associated with stays in medical institutions, especially hospitals. In most cases transmission was due to inadequate sterilization of equipment, as most hospitals used hot-air dryers in the almost total absence of autoclaves. High levels of nosocomially transmitted HBV (and also of HIV) have been reported from Romania and Russia.

2.6 Strategies for the prevention of hepatitis B As the examples of Poland and Bulgaria suggest, the prevention of hepatitis B infection requires that routine infant immunization is accompanied by other important measures such as the implementation of safe injection procedures, proper sterilization of medical and dental equipment, proper screening of blood, vaccination of health-care workers and people in the general population at high risk, the adoption of standard precautions in health-care settings, avoidance of the sharing of needles by injecting drug users and safer sex. Lack of funds in many countries means that blood screening programmes are not fully functional, equipment is not sterilized or is re-used inappropriately, and vaccines are not affordable. Many of the countries of central and eastern Europe and the NIS have prevalences of hepatitis B that pose substantial problems in terms of prevention and control but have very limited resources that are unable to cover all options. Sound epidemiological data and economic evaluation studies are needed to set priorities.

Strategies for the control and prevention of hepatitis fall into four main categories: 1. general preventive measures 2. universal precautions 3. passive immunization and 4. active immunization.

2.6.1 General preventive measures The general public, health-care providers and health-policy makers must be educated about the dangers of hepatitis B and other blood-borne infections. General preventive measures offer protection against not just HBV but other infectious agents as well and are focused on certain types of behaviour. Thus injecting drug users must be encouraged either to stop or to practice safer injecting techniques and be given access to sterilized needles. For all sexually active people, condoms will give considerable protection against HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. These measures need continuing education efforts targeted at people with high-risk behaviours.

2.6.2 Standard precautions Blood and body fluid precautions, usually referred to as standard precautions (and previously as universal precautions), stress that all patients should be considered to be infectious for HBV and other blood-borne pathogens and that measures should be taken to prevent exposure to all blood and blood-derived fluids. These precautions include the use of appropriate personal protective equipment such as gloves, gowns, masks and eyewear to prevent exposure to blood; the careful handling and disposal of needles and other sharp instruments; and the maintenance of a work environment free from contamination through use of appropriate disinfection procedures.

Various routes of transmission of HBV to patients have been documented, including transfusion of contaminated blood and blood products, use of jet gun injectors with a design fault that allowed blood to remain inside the equipment, re-use of contaminated needles and syringes, and indirect transfer from contaminated environmental surfaces in haemodialysis units. The contribution of unsafe injection practices to the burden of hepatitis B globally is unknown but likely to be substantial. Mathematical modelling supports this view: in a region with very high endemicity and in which infants receive 5 injections as part of their series of standard immunizations, nearly 40 infants out of every 1000 immunized could be infected with HBV if a needle is re-used 4 times before it is disposed of or sterilized.

Prevention of such transmission to patients includes general measures such as reduction in the frequency of unnecessary injections and of invasive surgical procedures, use of appropriate practices to screen blood donors (including screening for HBsAg), and use of appropriate means to inactivate and remove viruses in the manufacture of blood products. Infection-control procedures that can reduce the risk of HBV transmission include sterilization of all re-usable needles and sharp instruments, appropriate disposal of single-use needles and other sharp instruments, restriction of the use of multidose vials, and isolation of HBsAg-positive dialysis patients. Because of the risks outside the health-care setting, for instance through acupuncture, scarification, tattooing, circumcision, body piercing and dental work, the public needs to be informed about the risk of HBV transmission from invasive procedures with inadequately sterilized equipment.

2.6.3 Vaccination strategies 2.6.3.1 Selective vaccination After the first vaccines were licensed about 15 years ago, the prevention strategy was to vaccinate those people at high risk, such as health-care workers, homosexual men, injecting drug users, people with many sexual partners, mentally handicapped residents in institutions, recipients of multiple blood transfusions and infants born to HBV-carrier mothers.

The greatest impact of this approach has been the immunization of health-care workers. About three quarters of the countries in Europe now have a policy towards immunization of health-care workers. Clearly it is desirable to immunize health-care workers, but cases of HBV infection in this group account for only about 10% of those in the entire community.

Other countries had a selective policy of adult vaccination, targeting people at high-risk such as injecting drug users, homosexual men, patients on haemodialysis and in a few cases patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Most countries in western Europe applied a selective policy towards patients on dialysis but this practice was adopted by only a few countries in central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States.

The selective strategy for HBV control also includes the screening of pregnant women and treatment of the infants of carrier mothers. In 17 countries of the WHO European Region pregnant women are routinely screened for HBsAg and those who test positive are subsequently vaccinated. Nine countries have selective strategies. In 1994 Finland changed from a selective policy to one of routine screening. The Russian Federation and some Central Asian Republics have claimed financial constraints for not implementing routine screening of pregnant women.

Despite the prevention of many cases of HBV infection, it is clear that the strategy of immunization of those at high risk has failed. Several reasons account for this failure. These include: 1. The importance of disease due to HBV has been underestimated, and even physicians do not realize the burden of disease. 2. Most of those who have been vaccinated (e.g. health-care workers) make up only a small proportion of the total number of people infected and are not necessarily those at greatest risk. 3. Large groups of people at risk such as heterosexuals and homosexual men with multiple sexual partners and injecting drug users are difficult to target. In addition many people at risk (such as homosexual men and injecting drug users) are marginalized in society and either lack motivation to seek preventive medical interventions or actively distrust the organs of state responsible for prevention and health care. 4. About a third of the patients with hepatitis B have no identifiable risk factors and so would be missed by such a selective strategy. 5. There is a general lack of infrastructure for the delivery of vaccine to adults and there is a general failure of adult immunization. 6. The cost of hepatitis B vaccine is high. When the recommendation was made in 1991 for global introduction, hepatitis B vaccine cost about US$3 per dose, making a full course of vaccinations more than 10 times more expensive that all the other EPI vaccines combined.

2.6.3.2 Universal vaccination (a) Adolescents One approach to universal vaccination is the routine immunization of adolescents. This would have a more rapid impact on the incidence of hepatitis than routine immunization of children. Some, but not all, low endemicity countries are implementing (France, Germany, and Italy) or considering (Belgium and Switzerland) adolescent vaccination through the school health systems. Adolescents have on average less than one routine health-care visit each year compared with about 4 such visits a year for infants. Thus adolescents would need additional visits to complete the course of hepatitis B vaccination. Many countries do not have a system in place for vaccinating adolescents.

(b) Infants Universal immunization of infants is generally recognized as the basic strategy for long-term control of hepatitis B in areas of high and intermediate endemicity (and is preferred in most low endemicity countries). Infections during infancy and early childhood contribute disproportionately to the pool of HBV carriers. In much of the world infant immunization programmes are the only functioning vaccine-delivery systems (and there are several instances where civil wars have been suspended for national immunization days) and most countries have immunization-delivery systems that can provide immediate access to about 80% of the country’s newborns. The Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) is one of the public health success stories of latter years. In most developing countries hepatitis B would be best controlled by simple mass vaccination of all infants without the need to introduce expensive and complex programmes.

The World Health Assembly agreed in May 1992 that all countries should incorporate hepatitis B vaccination into their national immunization programmes by 1997. However, the implementation of new national programmes is not easy and needs careful consideration, especially from the economic point of view.

The five countries in central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States that have introduced hepatitis B immunization of infants into their national programmes are Albania, Bulgaria, Moldova, Poland and Romania. In all these five countries the introduction of hepatitis B vaccination into the national programme is now substantially reducing incidence rates. For instance, Bulgaria introduced mandatory universal immunization of all newborns and health-care workers at high risk in 1991 and has subsequently implemented further measures in its programme to eliminate HBV by the year 2020. No deaths from HBV infection in infants were reported in 1993-94 and no case was seen in an infant in 1995. In Poland immunization of newborns and infants of HBsAg-positive mothers was introduced in 1989; of health workers, medical students, nursery school children and laboratory technicians in 1990; of patients before operation in 1993; and for all newborns and infants in 1994-96 (starting in districts with highest incidences).

Introduction of universal vaccination should save millions of lives in the countries in the region, particularly in those where HBV is hyperendemic. In Turkmenistan the Ministry of Health has conducted a pilot study with follow up 4-6 years after a group of infants was vaccinated. Whereas in unvaccinated children HBsAg carrier rates of 7-17% were detected, the rate was 3% in the vaccinated 4-6-year old children. A similar picture was seen for anti-HBc. For e antigen none of the vaccinated group was positive in contrast to 19% of the unvaccinated group and anti-HDV was detected in none of the vaccinated group compared with 13% of the unvaccinated group.

(c) Infants, adolescents and those at high risk Further strategies include combined universal infant and adolescent vaccination, but this dual approach, while being highly cost-effective, needs the allocation of substantial resources. Once a universal vaccination programme is in place, efforts to vaccinate people at high risk of HBV infection should not be abandoned.

2.6.4 Promoting vaccination Convincing health planners, policy makers and the public of the need for hepatitis B immunization can be difficult. Clinical hepatitis B is more common in adults and consequently less popularly emotive than paediatric conditions and diseases such as acute respiratory diseases and diarrhoeal diseases. The case for preventive programmes will rest on the delineation of the disease burden, the proof of cost effectiveness, the raising of awareness and comprehensive prevention strategies.

Convincing providers and politicians of the need for prevention of hepatitis B is difficult. Five main elements contribute to the establishment of prevention of HBV transmission as a public health priority: · an understanding of the epidemiology of HBV transmission (and data presented at the meeting (see sections 2.5.2.3 to 2.5.2.5) have contributed significantly to our understanding of the epidemiology of HBV infection in Central and Eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States) · knowledge of the disease burden · clear cost-effectiveness of a vaccination programme · information and education campaigns, and · the development of a prevention strategy.

Obstacles remain. In many cases, the aetiology of chronic liver disease is not known and death may result from different causes. Policy makers have competing priorities. Information and education programmes are necessary to raise the awareness among professionals and public but these can be time-consuming (and costly); it may take some time to convince decision makers and doctors about the value of hepatitis B immunization (see, e.g., section 2.7.3 below). Hepatitis B immunization costs more than other EPI immunizations and the level of expenditure raises questions about sustainability of programmes. Nevertheless, negotiated prices have reduced the cost of vaccines substantially and together with a better understanding of HBV infection this has made universal immunization against hepatitis B cost-effective in different parts of the world.

In each country the steps necessary for the establishment of a national programme need to be identified and clearly set out. In principle, the actions necessary for the implementation of universal immunization are the same for every country. These are: · the fostering and sustaining of political commitment · the development of appropriate technical and procurement strategies · support for integration of HBV vaccination into the existing national immunization programme and · the evaluation of the impact of this integration of hepatitis B immunization.

Steps towards such action include the collaboration of health-care providers, government policy makers and the public in order to raise the necessary pressure. Awareness of HBV infection needs to be generated through education of the public, patients, those at risk, their care providers and medical specialists. The epidemiology and burden of disease must be understood, and for this to happen surveillance data are needed. Hepatitis B prevention and control then need to be accorded a high public health priority in order to win commitment and allocation of sufficient resources.

2.7 Priority setting The chances of success of a hepatitis B immunization programme depend of the priority it is given by a given government, its ability to implement such a programme, the cost, and a series of operational considerations.[4] The performance of all the immunization services will need to be reviewed and not only the school medical services but the private sector will need to be engaged.

Priority setting is not only a medico-scientific issue but also a political decision. In France, for instance, technical teams were evaluating the economic and epidemiological chances of success of hepatitis B immunization when the minister of health took a political decision in 1994 to adopt universal childhood immunization.

2.7.1 Disease burden With regard to disease burden, most morbidity and mortality is related to chronic HBV infection, but often the aetiology of chronic liver disease is unknown. Deaths may often be attributed to different causes such as gastrointestinal bleeding, sepsis or renal failure. In highly endemic areas, chronic liver disease is the leading cause of death (see, e.g., section 2.7.5), and so, for the development of strategy, the burden of disease needs to include deaths due to HBV (and HDV) as the basis for an economic evaluation.

2.7.2 Cost effectiveness Cost-effectiveness studies are necessary for various prevention strategies, but the fact that hepatitis B vaccine itself may be more expensive than all the other EPI vaccines combined presents a particular challenge for hepatitis B prevention. Policy makers are faced with competing public health priorities, from emergencies over cardiovascular diseases to outbreaks of infectious disease. In addition, the demands for sustainability require long-term planning for vaccine supply, whether through local manufacture or procurement. In the USA, for instance, data show that perinatal HBV prevention is more cost-effective than prevention given to adolescents, with a cost/year of life saved of US$1220 (see also below).

2.7.3 Information and education Prevention of hepatitis B will only be established as a public health priority when providers, policy makers, partners in development, patients and the general public are educated and informed about the benefits. Providers need to be assured about the safety of the vaccine, its efficacy and administration. Information about disease burden and cost-effectiveness will help persuade the policy makers.

In the USA it took a long time before decision makers and doctors were convinced of the benefits of hepatitis B vaccination. Immediately after the decision was made only some 30% of physicians (and 17% of family doctors) implemented it, but now the position has changed and as a result some 90% are immunizing all newborns.

2.7.4 Strategy The strategy is, quite simply, prevention through universal immunization of infants. The existing vaccines, whether derived from plasma or developed with recombinant antigens, are highly effective. Preventive efforts need to be focused (as the disease affects many age groups). Before any new vaccines can be considered by a government, the country must have an intact EPI system in place. Finally, the preventive strategy should include an overall plan of universal precautions for blood-borne pathogens (in other words covering nosocomial transmission and protection of the blood supply).

2.7.5 Disease burden in Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan In an attempt to help planners in Kyrgyzstan (where the annual health budget is the equivalent of US$400,000 or about $9 per person), researchers from the Hepatitis Branch of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysed mortality data for the Issyk-Kul oblast in Kyrgyzstan to determine the burden of disease in terms of disability adjusted life years (DALYs). As a proportion of mortality due to infectious diseases, the contribution of hepatitis B was small (about 3%) compared with the leading causes of death (acute respiratory diseases, other infectious diseases and diarrhoeal diseases) but when deaths from chronic liver disease were included and the data were expressed in terms of DALYs hepatitis B infection rose to become the second highest cause of death.

Among the almost 420,000 people in Issyk-Kul oblast in 1994 3614 deaths were recorded, most due to cardiovascular diseases. Interpretation in terms of years of potential life lost lessens the impact of these diseases, and application of the World Bank’s measure of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) does so even more.[5]

These data show how closer examination of morbidity and application of a recently developed methodology for assessing the impact of disease can lead to a much clearer picture of the burden of disease. A first step in determining health priorities is to ascertain the causes of morbidity and mortality. As in many of the Newly Independent States, mortality data in Kyrgyzstan, and equally for its constituent oblasts, are reasonably reliable, but data on morbidity are generally unavailable.

Arguments that are used to promote hepatitis B vaccine thus should be based on the prevention of a substantial proportion of preventable deaths.

2.8 Health economics Health-care budgets are limited and the increasing costs of health care mean choices have to be made in health-care provision. Health economists at the University of Antwerp (WHO Collaborating Centre for Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis) argued for economic evaluation, the finding of the optimal way of dividing scarce resources between the various health-care provisions, as a useful auxiliary instrument that can help in this decision-making process. Indeed, economic evaluation consists of the comparison of relevant alternative interventions with respect to both costs and effects, giving additional information for the setting of priorities and contributing to rational decision making.

When cost-effectiveness ratios were compared for various public health interventions in a country with a low endemicity for hepatitis B, it became clear that in terms of direct costs universal hepatitis B immunization is cost-effective. Although pertussis vaccination is cost-saving, universal hepatitis B immunization is more effective than varicella vaccination, cervical cancer screening and universal immunization against Haemophilus influenzae type b. Several studies in low-endemicity countries indicate that universal hepatitis B vaccination is cost-effective from the health care payers’ point of view.

In countries with high and intermediate endemicity, universal childhood vaccination programmes have been found to be cost-saving from the point of view of the medical care payer.

Although economic evaluation can indeed provide a rational basis for decision making, more standardization in the approach is needed, and it too depends on the defined burden of disease as well as the health-care infrastructure and vaccine-delivery system of a country.

2.9 Resource mobilization Existing infrastructures will allow an additional vaccine to those already in the Expanded Programme on Immunization to be delivered to almost the entire population of most countries within a year of its introduction. But even if a new vaccine were added, governments and donors are concerned about how to sustain both the infrastructure and the annual immunization coverage. This concern is not restricted to hepatitis B vaccine but to other vaccines that are being successfully developed but for which there is no guarantee of funding.

In the 1980s donors and partners in development had financially supported the entire supply of low-price vaccines for many developing countries, in the expectation that governments would work towards sustainability by gradually replacing external funding with their own resources. The advent of hepatitis B vaccine came as a shock and presented an uncomfortable prospect: the financial needs of national immunization programmes did not end with provision of the core vaccines; rather, these needs began with this supply. The problem will be compounded when a whole range of new and improved vaccines becomes available. Hepatitis B vaccine alone would be likely to increase vaccine budgets by a factor of three or four, and faced with this increase many donors decided not to support its provision for any developing country.

A review by the WHO in 1993 of progress in introducing hepatitis B vaccine into national programmes showed that, among the countries with strong immunization programmes and where hepatitis B was seen as a major health risk, those that were larger and had higher Gross National Products (GNPs) had succeeded in introducing hepatitis B vaccine into their programmes. Small and low-income countries had failed to obtain supplies of the vaccine. At roughly the same time UNICEF, a major purchaser of vaccines, explored its impact on the vaccine market and hence reviewed its procurement strategy. Together the two UN agencies developed a joint strategy designed to increase sustainability and to assist developing countries with new vaccines. This strategy comprises three elements: 1. increased government financing of the costs of immunization, particularly vaccines 2. assignation of priorities given to funding and support for needed new vaccines, and 3. assurance of affordable prices and availability of all vaccines. The new policy moves towards addressing the differences between immunization programmes, meeting the specific needs of each country and setting priorities for the use of the financial resources for immunization.

2.9.1 Increased government financing Countries that can finance their own programmes are being supported to become independent while help is being focused on weaker countries that need continued assistance. Three factors are used to identify the capacity of different countries to be self-sufficient: the relative wealth of a country (GNP per caput), the total population size, and a country’s “status” or “voice” in the international market place (i.e. GNP itself). In this way countries can be grouped into four bands (see Fig. 2):

Figure 2 : Sustainable vaccine supply : global targeting strategy for central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States (ref : State of the world’s vaccines and immunization (Bellamy C & Nakajima H, eds) World Health Organization & United Nations, Geneva, 1996

· Band A: those that need financial support · Band B: those that need some financial support but more importantly such services as help in planning, procurement and arrangement of flexible credit · Band C: those that have the wealth or size to become entirely self-sufficient in procuring or producing their vaccine supply but which need a one-off investment to help them become independent, and · Band D: those that can rapidly become independent with less external support.

Countries in Band A need continued support for their immunization programmes and vaccine supply. Without donor support their governments would not be able to maintain existing programmes let alone buy new vaccines. Nevertheless the strategy calls for these countries to start to set budgets, albeit small ones, for vaccines. Partners in development will help these countries access the new vaccines depending of the public health importance of the disease, the priority accorded to it nationally and the strength of the immunization programme. These countries include Albania and Tadjikistan (see Table 3).

TABLE 3 Sustainable vaccine supply: banding of countries for global targeting strategy

Source: WHO

Countries in Band B can become more independent in planning and financing their vaccine supply but would still benefit from services provided through mechanisms (such as the Vaccine Independence Initiative) which provide more flexible credit terms and support to procure vaccines. Those already producing vaccines will be provided with additional training in quality control, production, procurement and licensing as necessary. The target is for all such countries to be financing 80-100% of the EPI vaccine supply within 4 years. Band B includes Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Croatia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Romania, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Band C

countries will be offered one-time support with training for procurement,

establishment of national vaccine quality control systems, strengthening of

Band D countries (including all countries with GNP per caput greater than US$6000 per annum and which include Russia and Slovenia) need no continuing support but may become entirely independent with a single investment into their vaccine supply systems.

2.9.2 Setting priorities for funding and services Criteria have been agreed for countries that should have the highest priority for support for hepatitis B vaccine: · identification of vaccine as a priority for introduction (set out in the 1992 World Health Assembly resolution) · high burden of disease (>5% prevalence of HBsAg carriage in the population) · financial need (countries in Bands A and B) · strong immunization programme (at least 70% coverage with DTP3 immunizations) · government commitment (finance at least up to the sustainability target that has been set out for each Band), and · a decision by the Ministry of Health to introduce the vaccine. Countries meeting these criteria would be eligible for support to introduce hepatitis B vaccine. Band A countries would receive 90-100% financing. Band B countries would receive some form of matched funding phased over 3-4 years and be able to purchase vaccine at the low price negotiated by UNICEF. Band C and D countries would be responsible for procuring vaccine directly on open markets.

2.9.3 Affordability Historically UNICEF has been able to negotiate a price for EPI vaccines based on the manufacturers’ marginal costs but the industry has hesitated to allow such a formula to apply to new vaccines like hepatitis B. Nevertheless it appears that there is room for negotiation. Manufacturers have indicated that the lowest price based on marginal costing could be reached if the offer was limited to only the neediest countries and not applied to all developing countries, many of whom it is recognized could afford the prices that cover full costs. UNICEF’s tenders for 1996-97 reflected the new objective of early access to affordable new vaccines at affordable prices.

2.9.4 Support Besides the representatives of the various countries (see Annex 2) some donors and partners in development attended the meeting. These included the Rotary International, UNICEF, the US Agency for International Development (USAID), and the World Bank. (ECHO was invited but did not participate).

In terms of support for hepatitis B, “the door is not wide open, but it is not closed”, as a representative of one partner in development described it. Both donors such as USAID and manufacturers have accepted the banding system for financing routine immunization programmes. Partners in development recognize that it is of utmost importance that parties respect the system. Funds are available for training and partners in development have indicated their willingness to provide technical assistance and help in programme development.

Examples of support in technical assistance and support are several. USAID has provided assistance to many countries in the region since 1992 for the control of infectious disease, contributing US$35 million so far in technical assistance, vaccine equipment (including cold-chain materials) and most recently sustainability of immunization programmes. UNICEF has provided Romania with funds for a year’s supply of hepatitis B vaccine in a programme that includes elements of cost recovery and evaluation (through the CDC). Training in procurement of vaccines enabled Moldovan officials to produce a tender to buy vaccines that has been supported by the Japanese. Money has been invested in the Ukraine to prevent nosocomial HBV infections and to safeguard the handling of blood. In the Central Asian Republics programmes have been introduced through the CDC to help formulate and implement policies and programmes to control HBV infection. The WHO, CDC and VHPB can assist in the adaptation and application of a mathematical model to assess disease burden.

Some difficulties remain. There is evidence of “donor fatigue” and donors are increasingly responding to and interested in emergencies. Equally, donors may already have set, long-term programmes and priorities. For example, Rotary International continues its support for polio eradication but may only be able to apply its successful experience to hepatitis B when its polio programme ends in the year 2005. Meanwhile individual initiatives are always possible, however; its constituent clubs and districts are independent and some have initiated separate programmes for hepatitis B, for instance in Italy for Albania. For the Central Asian Republics support has been aimed at rebuilding the capacity to implement the original EPI programme with its 6 antigens; hepatitis B does not feature in the plans as there are limited funds and established priorities. A meeting of donors in Bishkek in 1993 heard of the problems of hepatitis B and called for data to be collected. These were presented at Siofók [see 2.5.2.3] but the issue now is how to implement policy? There are inevitable concerns about sustainability, especially in an era of increasing donor fatigue and multiple and growing priorities.

2.10 Workshops 2.10.1 Resource mobilization Several recommendations for national actions were put forward. 1. Countries should create a national “Task Force on Hepatitis B Prevention” whose composition should include leading, reputable physicians and academicians dedicated to the goal of prevention and control of hepatitis B. 2. Each government should draft a national Action Plan on Hepatitis B Prevention. The plan should include the following points: · a description of the size of the problem, that is: disease burden, health impact and economic burden. The CDC, Rotary International, UNICEF, USAID, VHPB, WHO, World Bank and other partners in development are prepared to offer assistance with this task. · preventive measures to be taken (e.g. immunization of health-care workers), with the ultimate goal of universal infant immunization. · a timetable for implementation (with a step-by-step approach, starting with high-risk areas and extending to broader regional areas and eventually country-wide coverage) with the final objective of a sustainable programme. · resource allocation, according to the timetable, with identification first of national resources and secondly of donor support necessary to complete the funding requirements; in addition there should be a plan for long-term sustainable national financing. (Reference to the WHO/UNICEF targeting strategy for sustainable vaccine supply, see section 2.9.1 above, indicates that countries in Bands A and B, with a prevalence of HBsAg carriers of greater than or equal to 5%, and EPI coverage of >70% and meeting the sustainability target for traditional vaccines, could expect donor support.) The national Action Plan for hepatitis B prevention should be closely linked to the primary immunization programme of the country to ensure its sustainability.

3. A broad consensus needs to be built, securing the highest possible political commitment for approval of the plan.

4. The approved action plan must be provided to the Ministry of Finance and potential partners in development (as well as national interagency immunization committees which exist; if they do not, then efforts should be made to create them).

Good examples of donor agreements to support the provision of vaccines for immunization programmes include the Nordic support to the Baltic countries and that of the Government of Japan to Central Asian countries in both of which instances the start-up phase has been financed by the donors and the national contributions are increased year by year until 100% financial self-sufficiency is reached.

5. The procurement of hepatitis B vaccine needs to be carefully prepared and executed (and in this area too the WHO, UNICEF, VHPB, USAID, CDC and other partners in development are able and willing to provide assistance). Issues to be considered include the choice of plasma-derived or recombinant vaccines: they are equally effective, immunogenic and safe, but plasma-derived vaccine are cheaper.

6. Successful results should be published at every opportunity. If financial problems threaten the programme, then the political implications and disadvantages of interruption of the programme need to be argued rather than the epidemiological risks.

2.10.2 Monitoring and surveillance 2.10.2.1 Lack of comparability of surveillance data between counties Five main problems hamper the comparison of surveillance data between countries. These are: · many countries only report jaundice, with no further aetiological diagnosis than “viral hepatitis”; most countries do not have a sufficient supply of diagnostic reagents to determine the aetiology, · there is no standard case definition, · the diagnostic criteria for the reporting of cases varies between countries, · the age structure of cases of hepatitis differs, as younger persons with hepatitis are less likely to be reported on account of their milder or asymptomatic illness, and · differences in case ascertainment: in some countries all people with jaundice may be admitted to hospital whereas in others only a small proportion may be so admitted. Cases not admitted to hospital are less likely to be reported.

2.10.2.2 Assessing the burden of disease due to HBV infections Four measures were identified that would enable the disease burden to be determined. These were: · data on the incidence of acute hepatitis B, which would be obtained from surveillance data; · the prevalence of chronic HBV infection (with data on pregnant women and children giving more reliable and representative information than surveys of blood donors); · the proportion of pregnant women who are HBeAg positive (which will give an indication of the contribution of perinatal transmission to the overall disease burden), and · the mortality rate from chronic liver disease as a result of HBV infection: i.e. cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

2.10.2.3 Monitoring the effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination programmes Three main surveillance methods are available to monitor the effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination programmes. The first provides data on vaccination coverage, with information coming from either registries or coverage surveys. A second measure consists of the changes in rates of acute HBV infection over time. Acute disease surveillance is a good means of monitoring disease in adults but not in children because asymptomatic infections in the latter would not be counted. Finally, one of the best measures of the effectiveness of routine infant immunization programmes is the change in prevalence of chronic HBV infection over time, with data coming from serial population-based seroprevalence studies of children.

2.10.3 Vaccines and immunization Review of the key characteristics of vaccines indicated that both plasma-derived and recombinant vaccines are safe and highly effective, meeting the requirements of the WHO. Both can be used in national programmes. Flexibility of scheduling allows these vaccines to be easily integrated into national programmes, and hepatitis B vaccine can be given safely with other childhood vaccines.

Routine immunization of infants with hepatitis B vaccine beginning at birth is highly effective against perinatal transmission of HBV. Administration of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) offers only a marginal increase in efficacy. Consequently, the addition of maternal screening for HBsAg and treatment with HBIG will greatly increase the costs of the programme with little increase in efficacy. Such a course is not recommended unless a country has substantial resources. Testing both before and after administration of vaccine is not recommended in national programmes.

Specific issues with regard to vaccine usage emerged. While it is acceptable to administer hepatitis B vaccine simultaneously with other vaccines, it is not acceptable to mix the vaccines, as some have to be administered at different sites. A new vaccine combining DTP and hepatitis B antigens may soon become available. When considering its possible use, countries should consider the following: · cost, · schedule (noting that hepatitis B vaccine will still have to be given at birth at which age DTP cannot be given; consequently the schedule of doses may become more complex), · the impact of the importation of the combination product on local production of vaccine.

It is not currently possible to adopt a 2-dose schedule for hepatitis B vaccine. Three doses are necessary to ensure high seroconversion rates and high antibody titres. With regard to booster doses, it was noted that some manufacturers argue in the literature accompanying the vaccine for a booster dose to be given at 5 years of age. At present, in view of the universal immunization programmes, there is no need for booster doses.

2.10.4 Vaccine production, quality control and regulatory issues Discussions drew on the expertise of representatives of vaccine-production facilities, national control authorities, and immunization programme managers in countries that procured hepatitis B vaccines directly or received them from UNICEF or other partners in development. With regard to the principles of quality control and quality assurance, the idea was accepted that quality means compliance with previously established requirements. The system of double control to which most vaccines in international commerce are subject includes a strict system to maintain consistency of production through application of Good Manufacturing Practice and in-process control by the manufacturer, as well as the independent control exercised by the National Control Authority.

The WHO has defined six essential national control functions that should be exercised in all vaccine-producing countries, namely: · a written system of registration and licensing for vaccines, · review of clinical data as part of the vaccine-evaluation process, · a system of lot release of vaccines, · a control laboratory for vaccine testing, · a system of inspections to ensure compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice, and · a system of surveillance to detect problems in vaccine performance in the field.

The exercise of these functions depends on the source of the vaccines. Whatever the source, there need to be a written system of licensing and surveillance of production units. Receipt of vaccines through UNICEF and procurement are the two major sources of hepatitis B vaccines for countries in central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States. In these cases, there is less or no need for clinical review, testing for lot by lot consistency or the testing of certain components. Instead the WHO maintains an additional system of control. Nevertheless, it is the responsibility of each nation to ensure that vaccines used in its immunization programmes are safe and effective. At the very least, national authorities must determine the specifications of the vaccines they use and monitor their impact.

Countries procuring vaccines must assume additional responsibilities. They must choose reputable sources of materials, adopt written requirements for vaccines (e.g. those produced by the WHO), and review lot production protocols for vaccine release. For many countries, however, the paucity of resources and the lack of experience are serious impediments to the implementation of such a system. As a result the following recommendations were made: 1. Countries should begin to institute mechanisms that ensure the quality of the vaccines used in their national immunization programmes. 2. To help in this process, the WHO can provide documentation and technical advice and also convene intercountry meetings to enhance regional collaboration. 3. Those countries with well developed National Control Authorities can serve as sources of expertise to countries now developing these systems and can provide laboratory support as needed.

2.10.5 Nosocomial transmission Previous differences in the definition of a nosocomial infection have been resolved, with acceptance of the following. A nosocomial infection: · develops during any health-care activity (and not only in hospital) · arises when a non-nosocomial infection under the above circumstances spread to a new organ system, or · originates from a nosocomially acquired pathogen even if the illness develops after the termination of the health-care activity.

HBV infection has a long and variable incubation period. Consequently, after only a short stay by a patient in hospital, the nosocomial origin of the subsequent HBV-related illness is hard to verify. Similarly, for health-care workers many possibilities of infection with HBV exist outside the hospital environment. As a result data on nosocomial HBV infections in either patients or health-care workers should be regarded as based on suppositions rather than proven facts.

There was no discussion of the introduction of vaccination of health-care workers where it is not already done as a high priority. (The European Parliament resolved in 1993 that all workers at risk of HBV infection should be vaccinated.) Rather the consensus was that, with only a few exceptions, hygienic measures could alone prevent health-care workers from being infected with HBV. The prerequisites are that the necessary safety equipment and clothing (such as high quality gloves and safe blood delivery systems) are available and that health-care workers are motivated to adhere to infection-control rules. Experience from some countries in Western Europe (e.g. Germany and Switzerland) shows that, despite the availability of all the necessary safety measures and a good awareness of the risks of infection, infection-control rules were only partially adhered to; it was only the fear of AIDS that motivated health-care workers to apply the rules more rigorously.

Good quality materials (gloves etc) are necessary, and in most, but not all, countries of central and eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States suitable equipment is available. The paucity of autoclaves, though, has already been noted (see section 2.5.2.6). In addition, compliance with infection-control procedures is also vital. This needs reinforcing, as the fact that the hepatitis B vaccine protects health-care workers from HBV infection may diminish their motivation to observe infection-control rules or universal precautions even though other blood-borne viruses follow the same route of transmission. Hepatitis B vaccination does not absolve health-care workers of the responsibility to observe infection-control rules.

Relatively little is known about transmission from patient to patient, especially in the countries of the region. With increasing injecting drug use in some of the countries and high prevalences of hepatitis B in some groups and minorities in the population, it is inevitable that the chances of contact between infected and uninfected patients will increase. Existing hygienic precautions need to be maintained but whether further measures for patients at special risk need to be taken remains an open point.